Lately, I’ve listening to a lot of FM radio. Car-related radio commercials form an interesting subgenre of ads. Two have stuck in my mind. The first is a Subaru ad, where a man talks about his romantic trips to a rural area with his girlfriend, and describes the feeling of watching other people drag their cars out of the mud. Luckily, the speaker will never be in that dishonorable position. He says, “I’ve never wanted to be the guy asking his neighbor for a push. That’s why I got a Subaru Legacy.” I mean, god forbid a man ever ask someone else for help, right?

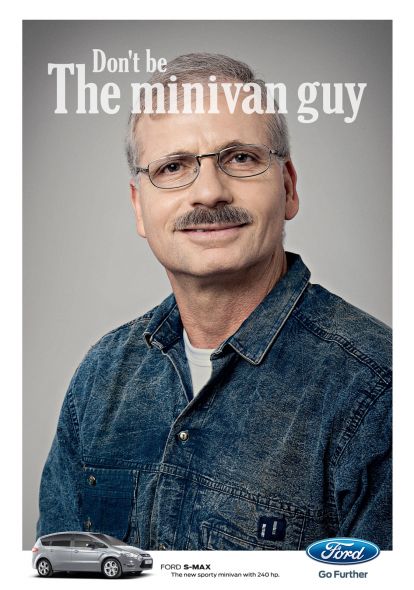

The other ad: A deep, masculine voice insists, “You didn’t buy that beige minivan to turn heads. So it’s embarrassing when your brakes squeak at every stop sign.” Is it really? Or is having squeaky brakes just part of owning a car, the natural result of regular driving?

Both of these ads exploit a perceived ideal of what it means to own and drive a car. My friend Julia suggested that the Subaru commercial might be trying to resist the brand’s lesbian associations, and I think there’s truth in that. The first ad I mention is about a man, providing for a woman, and asserting his self-reliance and independence from his neighbors. The second ad says, We know you don’t really want to drive a car that’s practical for parents, so you best not let people see you drive it. After all, if you were a truly independent man, you sure as hell wouldn’t be driving a minivan (or have any children to schlep around).

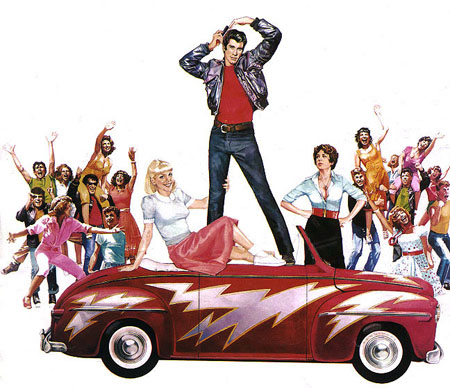

The automotive industry is built on masculine anxiety. This point hardly needs to be stressed. Consider the nostalgic representations of the 1950s, where a young man takes a woman out in his car for a night on the town. Consider Grease, where male sexuality is tied to the power of an engine. Consider Top Gear, Pimp My Ride, or the notorious car collections of Seinfeld and Leno. As a cultural icon, the automobile embodies men, power, and independence.

There was a time when the car was the Great American Object. Once Henry Ford figured out the assembly line, and made cars increasingly accessible, to be young and free (and male) was to own and operate an automobile.

Recently, cars have been losing their cachet. In a 2014 poll by Zipcar, most Millenials would rather sacrifice a car than a smartphone. Social media has changed how we connect with one another, and smartphones have driven these developments. Phones can integrate themselves into our everyday lives in ways that computers can’t. Roughly speaking, computers are to phones as railroads are to cars. Trains were a crucial development in transportation, but they weren’t the distinctly American icon that cars turned out to be. And pretty much everyone can have a phone. Compared to cars, phones are cheap to buy, easy to use, and cost little to maintain. For many low-income people (and plenty of others), phones are the main way of getting online. Of course, most people can afford smartphones because they agree to pay phone companies for years of service. But, relative to cars, phones are a pretty good deal.

Smartphones represent something markedly different than automobiles. Social media is all about being connected, relating to others, sharing information. No more are our objects designed to provide independence and freedom, but to create new forms of interaction and community.

How are smartphone users gendered? Pretty feminine. Think of the iconic teenage girl using all of her family’s monthly minutes, a gendered archetype that’s been around since before the phone scene in Bye Bye Birdie. In The Honeymooners, it was Alice, Ralph Kramden’s wife, who wanted a phone in the house. The 2013 song “#Selfie” features a female voice declaring that she must use her cell phone to document every moment of her night out. And yet the associations of smartphones aren’t nearly as aggressive as with cars. Publications such as Wired and TechCrunch demonstrate how modern technology can very much be something for men. BUT, consider how smartphones become masculine: as a business opportunity, a thing to “hack,” a problem to be solved. In the world of smartphones, men are always a step ahead, looking for emerging markets and “disruptive” apps.

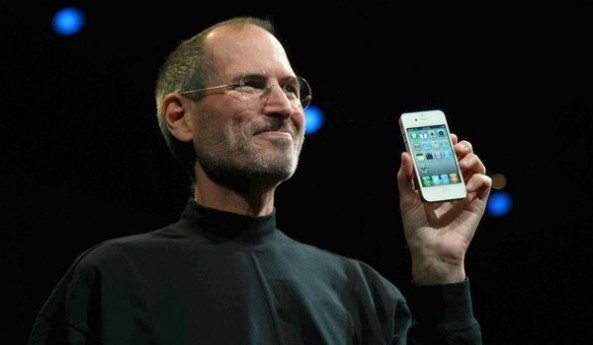

Consider the image of Steve Jobs, the forefather of startup fetishism, standing on that stage holding an iPhone. This man, like Henry Ford, is distributing a gift, an object that will change our lives. And all the big names in tech innovating are men — Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, Elon Musk. Even when it comes to products and platforms meant to connect people, it’s the individual (male) entrepreneur that gets the most credit.

Of course, claiming either Henry Ford or Steve Jobs as solely responsible for their products is completely dishonest. Henry Ford’s great development was the assembly line — a means of getting other people to do a lot of work, in a particular way. And Jobs made the smartphone so widely accessible by employing masses of workers to do mundane labor overseas, often in despicable conditions that we would never accept in the United States. The fantasy that any single person is wholly responsible for an invention is always false. After all, someone (probably a woman) had to wipe baby Mark Zuckerberg’s ass.

Okay, so clearly the smartphone (and truly I mean the iPhone, as all smartphones are a facsimile of that Apple icon), maintain some gender distinction between male producers/innovators and female consumers. But this divide is much less strict than we see in Subaru’s masculinist radio commercials. iPhone ads are known for the simplicity and blankness meant to make their product appear “universal.” But Apple actually goes beyond universality, as their advertisements foreclose on the possibility for the world to exist outside of their products. Their advertisements co-opt the language of change and revolution, proclaiming the only relevant social progress is the latest advances of tech.

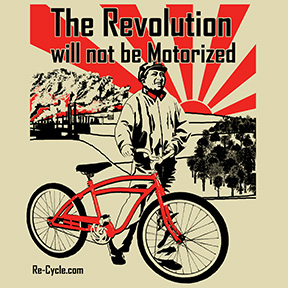

When I was in high school, I hated cars. Of course, I grew up in Brooklyn, so I never really needed one. But. crucially, I had a bicycle. Riding my bike kind of became my thing in high school (and every teen loves to have a thing). Cycling was more than how I got around. I interned at the nonprofit shop Recycle-a-Bicycle and learned to build my own bike. I rode my bike to Occupy Wall Street, and saw how people were directly, physically, challenging hierarchies of power and privilege. The summer after my first year in college, I interned at Bike New York, and learned to teach kids how to ride bikes safely.

Bicycles came to me at a good time in my life. For a teen, bikes were risky enough to be thrilling, but also provided exercise, and the opportunity to learn about my own interest. Several of my best friends were also into bikes, and riding allowed us to explore and connect with the city. Bike lanes and bike parking gave me causes to care about. I saw how cycling could immerse itself into the geography of a city, and mold a space into something better than it once was.

Cycling is queer as hell. While yeah, bikes are marketed to specific genders, and certain jobs (bike messenger, tour de Francer) are more reserved for men, the bicycle subculture connected me with people of all genders and sexual identities. But, more importantly, bicycles can challenge hegemonic power. A human on a bicycle is the most efficient machine on Earth. As Bill Nye said, “A bowl of oatmeal, 30 miles, you can’t come close to that. Put a bowl of oatmeal in your car, you’re not going anywhere, let alone 30 miles.”

Most (good) bike shops are local businesses, and there’s a thriving market of bikes and bike parts on Craigslist and other peer-to-peer platforms. Bikes are something people can pretty easily fix and maintain themselves (as cars perhaps once were). Bicycles are powerful, beautiful, and revolutionary.

So what does this have to do with phones? Physical transportation is classified by those who have the most power. After the decline of U.S. railroads, car companies dominated American culture and led to the development of massive highway systems that completely shape the way we engage with space. In American cities, streets are designed for driving, or walking, with public transportation as an often positive — but bureaucrat and infrastructurally complex — alternative. But bicycles demonstrate how people, as individuals and collective communities, can imagine and create cheaper and more environmentally-friendly ways of moving through space. Can there be any equivalent object for smartphones? Like the automotive industry, tech is defined by gendered relationships of power. Is there some way to live through and within digital space without supporting exploitative labor, oppressive contracts, and economic precarity? Apple wants us to believe that tech innovators are responsible for all social change and progress. But we need not wait for a white man to tell us when – or how – to go.